The Structural Dissociation Model

Dissociation is on a spectrum ranging from daydreaming to DID (Dissociative Identity Disorder – formerly known as Multiple Personality Disorder).

Being in a normal dissociative state means we go onto automatic pilot when doing an activity, such as when we are driving a car and not having to pay a lot of attention to what we are doing. More complex dissociation means to develop a strategy of managing our emotions with techniques such as repression.

Different Parts of Us

The Structural Dissociation Model explains how the psyche becomes more fragmented under extreme stress. It is based on the defences we share with mammals – these are; fight, flight, freeze, submit and attach. In someone who has not had significant trauma these defences will be more integrated. When a child is growing up in a position of extreme stress with an unsafe parental figure, the mammalian defences will become less integrated and more compartmentalised as shown in the diagrams below.

When we are under threat our bodies are triggered into action and we will either go into hyperarousal (fight or flight) or hypoarousal (freeze or submit). These responses help us to either fight, run, play dead or fawn. The attach defence helps us to attach to other people or to get help from other people. Our defence mechanisms are tailored to our life experiences and to what has previously worked best for us in situations where we have felt under threat. Our responses become ingrained and automatic.

These different parts of the personality will each develop their own defensive roles which are seemingly independent and self-governing. For example:

- Fight is a hypervigilant soldier on the lookout for danger at all times. This means some people can struggle to relax, or switch off their mind

- Flight uses addictive behaviours to get relief from painful feelings by ‘turning off’ the body

- Submit helps us to blame ourselves, go along with others and put our own needs last. We may dislike ourselves for being so people pleasing or unable to stand up for ourselves

Please also see The Brain and Trauma which explains how the brain works under stress.

Types of Dissociation

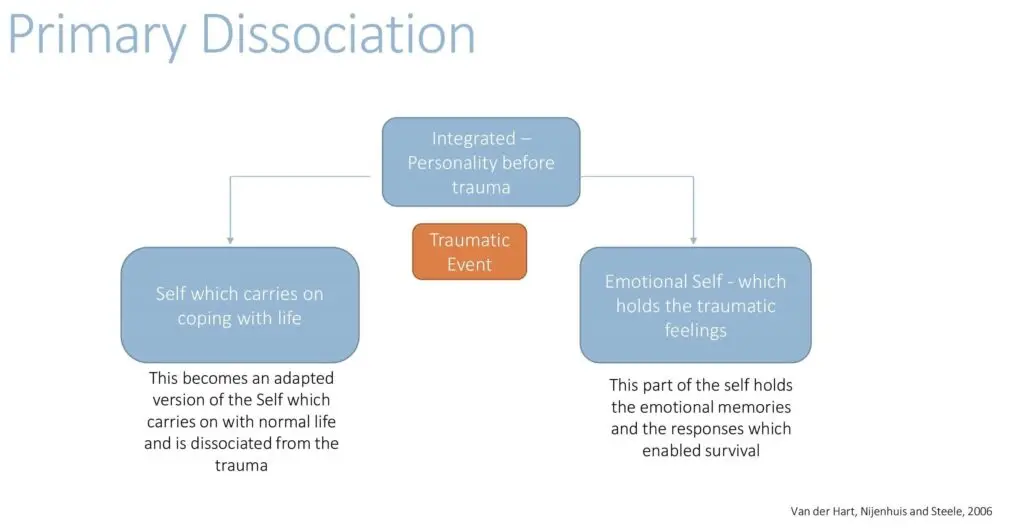

Primary Dissociation

Primary Dissociation can occur from a single traumatic incident like a car accident.

A split in the psyche helps us to manage an incident that feels overwhelming.

Traumatic memories are recorded in the right hand brain, which can be considered to be the emotional part of the brain, outside of our conscious awareness in the form of images and feelings and the behavioural response that was used is also recorded.

The left hand brain, which can be considered to be the logical part of the brain responsible for reasoning, learns, organises and makes meaning from events. It is also the observer of our lives. This part of our brain can carry on with normal life largely consciously unaware of the trauma that has happened.

Secondary Dissociation

Secondary Dissociation can occur when a person is subjected to prolonged trauma or neglect from which they cannot escape.

They may have grown up with a caregiver who had issues which affected their ability to parent. Their caregiver may have had a personality disorder, been in addiction or had their own unprocessed trauma.

In secondary dissociation, the emotional part of the personality becomes more fragmented and split. These subparts then evolve to reflect the different strategies needed for survival.

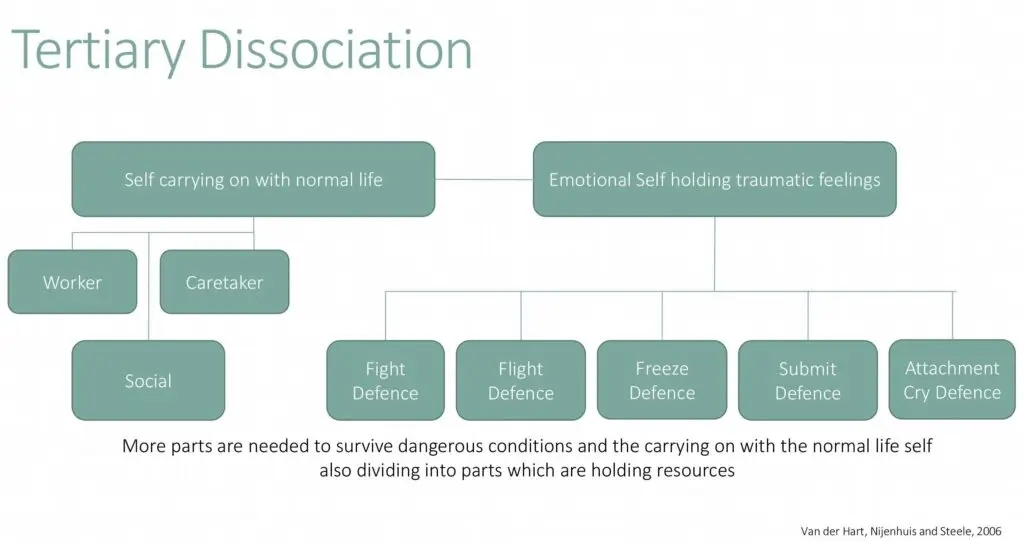

Tertiary Dissociation

Tertiary Dissociation happens when even more survival responses are needed and the ‘going on with normal life’ self can also be fragmented into subparts consisting of worker, caretaker and social parts. Here we can find Dissociative Identity Disorder.

Hyperarousal

“If an individual is born into a malevolent world it is crucial for survival to maintain a state of vigilance and suspiciousness that enables him to readily detect danger.“

Tiecher et al, 2002

Recognising the Different Parts of the Self

Dissociated Defensive Parts Help us to Quickly Respond to Danger

When we have come from a dysfunctional background, our brains and bodies are primed for danger and will be triggered by cues in the environment which remind us of previous situations which have been dangerous.

Please see Triggers and Triggering which explains common danger cues and what dissociative reactions to those cues feel like. The clues to our being triggered can be found in our bodily responses. Triggered reactions are sudden and intense and hard to change once they have taken hold.

Structural dissociation can be likened to a honeycomb structure where different survival strategies and traumatic feelings and memories are stored in fragments in different compartments. They may not have conscious awareness of each other until some healing has taken place.

This means that the personality has a ‘going on with normal life self’ (the self you know as you) and these other defensive parts which are stored in the subconscious ready to be brought into action when needed.

These parts of the self are generally ‘frozen in time’ at the time they were created and they tend to respond to situations as though the old trauma, which was happening when they were created, is happening now. Many of these parts may feel childlike or teenlike.

Recognising defensive parts in the body

Fight can show itself as tension in the neck, arms and shoulders (the muscles are aching as they have been clenched).

Flight can show itself as agitated movements in the legs and feet and/or sitting on the edge of a chair (the body is prepared to run).

Freeze can show itself if the body becomes very still, breathing stops or the eyes widen.

Submit shows itself in hunched shoulders, not wanting to make eye contact and the head hanging down.

The Attachment part can show itself in the eyes, hands, and head being orientated towards the source of help.

Recognising defensive parts in emotions and thoughts

Fight is a protector and can be mistrustful and devaluing.

Flight has addictive behaviours and/or the desire to run away. Also may feel trapped and unsafe.

Freeze is terrified and can have panic attacks. Feels fear and has beliefs related to danger and annihilation.

Submit feels ashamed, hopeless and full of self-hatred. It has a fear of displeasing and is people pleasing.

Attach feels needy, desperate and is childlike and dependent. It wants to feel close and fears abandonment. It yearns for someone to come.

Dissociation

“Dissociation refers to a compartmentalisation of experience: elements of an experience are not integrated into a unitary whole but are stored in isolated fragments….Dissociation is a way of organising information.”

– van der Hart, van der Kolk and Boon, 1998

The Neurobiological roots of Dissociation

by Janina Fisher PhD

“Human infants begin life with an immature brain and body, lacking the capacity to regulate their biobehavioral states without the external mediation of their caretakers.

Ideally, during this stage of development, attuned parents interactively regulate babies’ dysregulated states, helping them expand their capacity to sustain positive moods, recover more quickly from dysregulation, and communicate via social engagement their physical and interpersonal needs (Putnam, 1997; Shore, 2004; Ogden et al, 2006).

Our capacity for affect tolerance and the achievement of an integrated sense of self later in life is dependent upon these self-regulatory abilities acquired during early development, both the ability for interactive regulation (to be soothed by others) and auto-regulation (soothing ourselves).

In addition, because dysregulated autonomic arousal inhibits activity in the prefrontal cortex (LeDoux, 2002), even the child’s ability to learn, problem-solve, and verbally communicate is dependent upon self-regulatory capacity and therefore on the quality of early attachment.

Without interactive regulation from securely attached parents, small children must depend on their ability to alter consciousness when soothing is needed and on the body’s innate “fault lines” for compartmentalizing overwhelming experiences (Van der Hart, Nijenhuis & Steele, 2004; 2006).”

This is an extract from a document named ‘Structural Dissociation’ which can be found on the web, by Janina Fisher PhD, which explains the neurobiological background to dissociative disorders and how they can be treated.

Janina Fisher’s website – PDF downloads available here on understanding trauma.